If you have experienced symptoms from working in a moldy work environment, you might think you are entitled to recover from your employer. However, navigating the Workers’ Compensation system can be challenging partly because of the distinct and often complicated vocabulary in the statutes. This case involves defining an occupational disease under the Louisiana Workers’ Compensation Act.

If you have experienced symptoms from working in a moldy work environment, you might think you are entitled to recover from your employer. However, navigating the Workers’ Compensation system can be challenging partly because of the distinct and often complicated vocabulary in the statutes. This case involves defining an occupational disease under the Louisiana Workers’ Compensation Act.

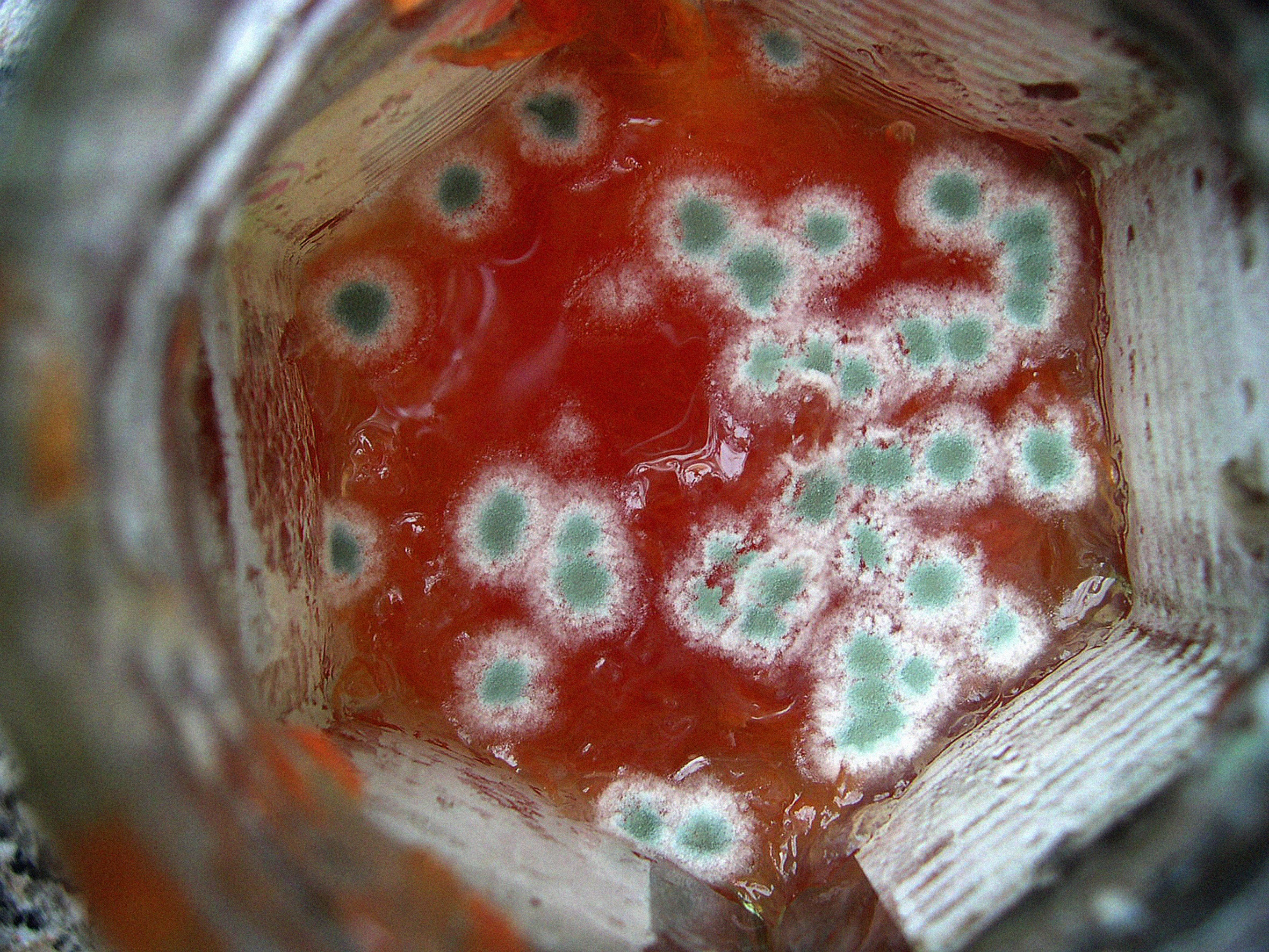

Angela Lyle worked in the payroll department at Brock Services. Her office was in a trailer in Norco, Louisiana, at the Valero plant. Lyle claimed she saw mold throughout the trailer that increased over the two years she worked at the site. She suffered from fatigue, burning eyes, sores, and other symptoms. After suffering a nosebleed, she underwent a medical evaluation. Testing confirmed mold was present in the office, so Lyle’s trailer was replaced. Once the trailer was replaced, some of Lyle’s symptoms went away, but others persisted, and new symptoms emerged.

She resigned and was diagnosed with sarcoidosis in her lungs and lymph nodes. She then filed a claim with the Workers’ Compensation, claiming she had suffered an occupational disease and was entitled to damages. The workers’ compensation judge denied her claim as neither her mold exposure nor the development of sarcoidosis qualified as an occupational disease or accident under the Louisiana Workers’ Compensation Act. Brock filed a summary judgment motion, arguing Lyle could not establish sarcoidosis was an occupational disease. The workers’ compensation judge granted Brock’s summary judgment motion, finding Lyle’s sarcoidosis was not an “occupational disease. Lyle appealed, arguing the workers’ compensation judge ignored the definition of an “occupational disease” under the Louisiana Workers’ Compensation Act.

La. R.S. 23:1031.1(B) defines an occupational disease under the Louisiana Workers’ Compensation Act. The court considers an employee’s work-related duties to determine if an illness is an occupational disease. On appeal, Lyle argued in a recent court case, Arrant v. Graphic Packaging International, Inc., the Louisiana Supreme Court held causation was the primary determinant of whether a claim is compensable as an occupational disease. She argued that this connection between the employment environment and the claimant’s illness was different from the prior duties-based approach, which required a causal link between the claimant’s illness and the claimant’s work-related duties.

The appellate court disagreed with Lyle’s interpretation of Arrant and held there had to be a causal link between Lyle’s illness and her work-related duties. Therefore, the appellate court agreed with the workers’ compensation ruling that granted Brock’s summary judgment motion and dismissed Lyle’s claim.

If you or a loved one have experienced an illness you think resulted from your job, a good attorney can advise you on the requirements to prevail in a claim under the Louisiana Workers’ Compensation Act. This can include presenting evidence to support a causal connection between the illness and your job duties. Otherwise, even if you have been working in a potentially harmful environment, like Lyle’s moldy trailer office, you might be unable to recover.

Additional Sources: Angela Douglas Lyle v. Brock Services, LLC

Article Written By Berniard Law Firm

Additional Berniard Law Firm Article on Causation in Workers’ Compensation Claims: The Challenge of Establishing Causal Links in Workers’ Compensation Claims

Even in cases involving tragic factual situations, strict procedural requirements must be followed to prevail on your claim. This case involves the time limits in which you must file a lawsuit and the principle of

Even in cases involving tragic factual situations, strict procedural requirements must be followed to prevail on your claim. This case involves the time limits in which you must file a lawsuit and the principle of  Statutory employer immunity is critical in determining liability and compensation for workplace injuries in workers’ compensation. The following case is an example where the court had to decide whether the defendant was entitled to statutory employer immunity under the dual contract theory provided for in

Statutory employer immunity is critical in determining liability and compensation for workplace injuries in workers’ compensation. The following case is an example where the court had to decide whether the defendant was entitled to statutory employer immunity under the dual contract theory provided for in  Summary judgment is designed to enable judicial expediency and cost-effectiveness in the courts. It is an important and complicated procedure that can occur repeatedly during litigation. When summary judgment is asserted repeatedly in the same case, how do parties prevail in their attempts to get or defeat summary judgment motions? The following case helps answer that question.

Summary judgment is designed to enable judicial expediency and cost-effectiveness in the courts. It is an important and complicated procedure that can occur repeatedly during litigation. When summary judgment is asserted repeatedly in the same case, how do parties prevail in their attempts to get or defeat summary judgment motions? The following case helps answer that question.  When an individual sustains an injury while on the job, the anticipation of receiving workers’ compensation to tide them over during their recovery is natural. Regrettably, situations arise where companies are unwilling to shoulder this responsibility. The scenario becomes more intricate when a parent company distances itself from its subsidiary’s actions, attempting to evade liability for workplace injuries. This particular Louisiana Court of Appeals case delves into corporate responsibility, illuminating the circumstances under which a parent company is held accountable for the safety measures enacted by its subsidiary entities.

When an individual sustains an injury while on the job, the anticipation of receiving workers’ compensation to tide them over during their recovery is natural. Regrettably, situations arise where companies are unwilling to shoulder this responsibility. The scenario becomes more intricate when a parent company distances itself from its subsidiary’s actions, attempting to evade liability for workplace injuries. This particular Louisiana Court of Appeals case delves into corporate responsibility, illuminating the circumstances under which a parent company is held accountable for the safety measures enacted by its subsidiary entities. Louisiana’s Workers’ Compensation fund exists to pay employees injured at work. Payment can be used for medical care and lost wages. When parties sign a settlement agreement on payment terms, an employee may assume payment is imminent. In a recent case from Rapides Parish, an employee discovered some conditions in a settlement may delay payment.

Louisiana’s Workers’ Compensation fund exists to pay employees injured at work. Payment can be used for medical care and lost wages. When parties sign a settlement agreement on payment terms, an employee may assume payment is imminent. In a recent case from Rapides Parish, an employee discovered some conditions in a settlement may delay payment.  Injury in the workplace can usually be avoided with proper safety measures in place. Safety measures, however, become hard to enforce when minors and adults work in conjunction. This was the case for Austin Griggs, an illegally employed minor injured in a forklift accident while working.

Injury in the workplace can usually be avoided with proper safety measures in place. Safety measures, however, become hard to enforce when minors and adults work in conjunction. This was the case for Austin Griggs, an illegally employed minor injured in a forklift accident while working. Unfortunately, accidents in the workplace are not uncommon. What happens, however, if you unknowingly signed an agreement making your employer immune from a liability claim? The following Lafourche Parish case outlines this predicament.

Unfortunately, accidents in the workplace are not uncommon. What happens, however, if you unknowingly signed an agreement making your employer immune from a liability claim? The following Lafourche Parish case outlines this predicament.  When you think about sexual harassment claims, the first thing that likely comes to mind is a superior harassing another employee. However, what happens if the superior instructs another employee to date a prospective client?

When you think about sexual harassment claims, the first thing that likely comes to mind is a superior harassing another employee. However, what happens if the superior instructs another employee to date a prospective client?  If you do a favor for your boss outside of work and are injured, can you still sue for workers’ compensation benefits? This is a complex question dependent on the facts of a case. Workers’ compensation is only available for injuries suffered during employment. If the court finds that the favor was outside the scope of employment, an injured employee may only recover tort damages. In the following case, the appellate court reversed a finding of workers’ compensation in favor of tort liability. In this case, the injured worker fought against a reduction of award to offset the workers’ compensation benefits already paid to the plaintiff.

If you do a favor for your boss outside of work and are injured, can you still sue for workers’ compensation benefits? This is a complex question dependent on the facts of a case. Workers’ compensation is only available for injuries suffered during employment. If the court finds that the favor was outside the scope of employment, an injured employee may only recover tort damages. In the following case, the appellate court reversed a finding of workers’ compensation in favor of tort liability. In this case, the injured worker fought against a reduction of award to offset the workers’ compensation benefits already paid to the plaintiff.